Beyond and Back: Protest the Dams

During such dire times as we are in now, I would like to pass on this story I wrote in 2008. It is an outtake from the book 180° South. It has never been published. During the making of the film I spent a few months down in Chile hanging out with fishermen and gauchos and land conservationists. I was honored to have heard their stories told around campfires, sitting beneath the stars with the sound of rivers flowing nearby. I saw with my own eyes where the dams are to be built and the land and livelihoods that are threatened. Along with this story I’ve attached photographs I’ve taken of people who are on the front lines and who have much at stake. Some of these photographs have been published and some haven’t. I want to thank them and all of you who have risen to the occasion. The fight is not over.

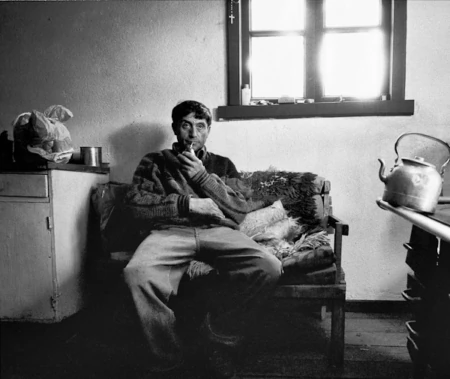

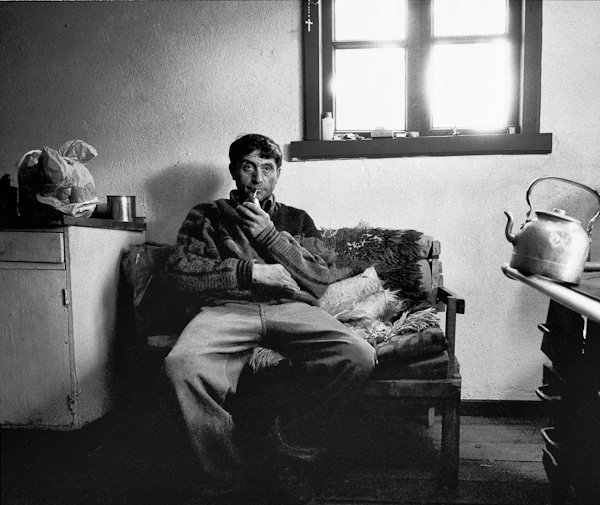

Gaucho Eduardo Castro. Valle Chacabuco, Chile. All photos © Jeff Johnson

Valle Chacabuco

It was early. The sun was still behind the mountains. I was stuffing my sleeping bag into my backpack when one of the gauchos approached me.

“Café?” he suggested as he handed me a leather bota bag. “Es bueno.”

“Sure,” I said as I offered one of the three Spanish words I know. “Gracias.”

I lifted the bladder up high, tilted the nozzle over my mouth and squeezed. I coughed, spat and bent over, rolling the liquid around in my mouth. I wasn’t expecting red wine.

“Café?” I asked, wiping my mouth off.

“Si,” he said with a laugh, “Café rojo.”

I took another mouthful. “Si,” I said, “Bueno.”

After multiple ferry rides, two days driving on dirt roads, we have arrived at Estancia Valle Chacabuco, in remote Patagonia. Kris Tompkins, as part of the Patagonia Land Trust, purchased the former sheep and cattle ranch in 2004. Overgrazing had taken its toll on the land so all the farm animals have been relocated. The goal is to restore healthy soils and open wildlife corridors by removing the 450 miles of fence line that winds through the 170,000 acres of mountains and valleys. The Patagonia clothing company has a program that encourages its employees to volunteer three weeks of their time down here, pulling up fences, all expenses paid. Makohe, Keith, Yvon and I showed up just in time to put in our time as well.

Leaving the bunkhouse at Casa De Piedra we were led on horseback by gauchos across Chacabuco Valley. We crossed a series of rocky river beds, waded through deep icy rivers and entered a smaller valley to the northeast. The gauchos broke trail up the left side rising above a box canyon. I could hear river rapids echo through the valley while a small group of huemul deer scampered up the hillside. On a bluff protruding from the valley wall we made camp and spent the day pulling up old fence posts and barbwire that ran from the top of the canyon wall down to the river.

That evening, all of us lay in front of a fire, warming our toes and gazing up at bright constellations. Asada, skewered with broken tree branches, sizzled and popped over open flame. Gauchos Alfonso Ruiz and Erasmo Betancore sat on a log with an accordion and guitar and played local folk music. In between songs Erasmo talked about the proposed dams along his beloved Rio Baker. I wasn’t shocked to hear that no one had told the locals about the project, not the government or the construction companies, until it was too late. As a result, the locals in the region have started a grassroots campaign called Sin Represas, which means, “without dams.” One gaucho claimed that it’s a cause, “worth dying for.”

Gaucho Alfonso Ruiz. Valle Chacabuco, Chile.

Gaucho Erasmo Betancore. Valle Chacabuco, Chile.

“This is devastating,” said Erasmo, “Not necessarily for me, but for the family I leave behind. This is the problem: there are people in Santiago, or other cities, who don’t have love for Patagonia… but in reality we grew up here and live here. A lot of times Patagonia is a place they can sell or give as a gift, as they have already done.”

One of the biggest social and environmental issues in Chile is the damming of rivers. During the reign of dictator Pinochet, Chile awarded the water rights to most of their rivers to private enterprise. In turn, a Spanish energy company named Endesa has been systematically introducing energy projects like river dams all over Chile. One such project calls for five hydroelectric dams along the Rio Baker. The Baker is the largest free-flowing river in Chilean Patagonia. The livelihoods of many people depend on it. Like Ramón Navarro said about the pulp mill: “Constitución was one of the most culturally rich places in Chile. But when the cellulous mill came, it killed everything.” The same goes with the dams.

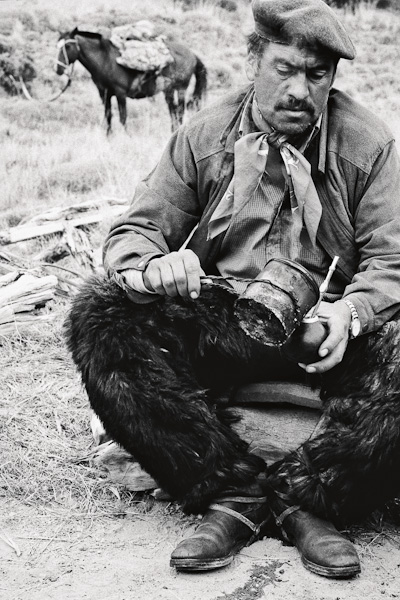

Crab fisherman. Near the town of Cobquecura, Chile.

The plan is to supply electricity to big cities, which means bulldozing a strip to run high-tension wires for 1,300 miles all the way up the length of the Patagonian Andes to Santiago. If the project moves forward I was told it would be the largest clear-cut area in the world. Hydroelectricity is much safer than nuclear energy but it’s not without consequences. It’s extremely complicated though. I don’t have the answer. There’s got to be some new alternatives other than the antiquated technology of dams. What happened to wind? Or solar? Some say they aren’t as efficient. But have we really put in the time and effort for something better? Most of the problem, I believe, has to do with the increasing demand. Change has to start with us, the consumers.

My trip started six months ago with a dream of getting away from it all: find some un-ridden waves and climb something that’s never been climbed. But it’s been much more than that. It began in Yosemite Valley – a National Park that was saved because a man named John Muir took President Theodore Roosevelt into the backcountry and convinced him that it should be protected. I spent time in the Galápagos Islands, a preserve where animals rule the land. I saw what happened to Rapa Nui when people lost touch of basic living and depleted their resources because of superfluous needs. I hung out with Ramón Navarro, a guy who has dedicated his life to preserving his homeland. And my journey neared its end in Valle Chacabuco, Chile – another chunk of wild land that was threatened and now saved by a few concerned individuals. I’m seeing that even the most remote places are under pressure and the biggest threat we humans face is ourselves. And the ones who make the biggest difference in this world are not governments or big corporations, but people, individuals who care enough to fight for it.

Crab fisherman. Near the town of Cobquecura, Chile.

In the morning I washed my face in the creek next to camp and drank water from a clear, silver-blue pool. I stood up and Erasmo was there with the bota bag in his hands.

“Café?” he said smiling.

“Si,” I said, wise to his trick now.

As I tilted my head back to drink I caught eyes with him. Whether sharing mate or wine he always makes sure he has eye contact with you, a bonding perhaps, as if to say, it’s you and me out here, together. I drank some of the café rojo. Erasmo did the same. I watched as he returned to his horses, strapping saddlebags to them while eating a small piece of cold asada. Everything he does is automatic, it’s in his blood, and it has been that way for generations. But his simple way of life is fading. I come from a place much different than Erasmo’s – a consumer society where we often use more than we need. The toxic pulp mills along the Chilean coast are making products I use back in the states. Dams are sending electricity to places I live or have traveled to. Our needs are much larger than his. And his rivers are being dammed because of someone’s greater needs elsewhere. Now, I must catch myself. Every time I find myself using more than what I need, I know that someone, somewhere, might be losing everything.