Ask Where the Mules Go

Following ancient pathways in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains.

According to our local guide, Samir Ahmoudou, to travel anywhere in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, you only need to know three Amazigh words: sow, gow, ich—“eat, sleep, drink.” Hospitality will take care of the rest. Such advice seems simple to the point of unlikely, but the piles of fresh bread and pot of fragrant mint tea in front of us attest to its validity. Samir sits across the table and settles onto the brightly colored pillows as breakfast arrives: two cone-shaped earthenware pots—called “tagine” and full of egg stew—pumping out steam like mini volcanoes.

We’re in the village of D’ouzrou, and the man serving the dishes is Hamid Ashtouk. He works at our nearby guesthouse and invited us into his home as we passed on our morning ride. Two dishes feed all of us: my friends Leslie and Chris Kehmeier from Colorado, and our new friends and guides, Pierre-Alain Renfer, Hassan Bezzazi and Samir.

Our trip in Morocco is nearing an end, but it is our first day with Samir. The 26-year-old usually leads trekking trips but recently picked up mountain biking and became fascinated by this fresh mode of recreation. He’s labeled today’s ride as “explorative,” the subject of the exploration being more of the Atlas’s heritage trails. They’re what drew us here in the first place.

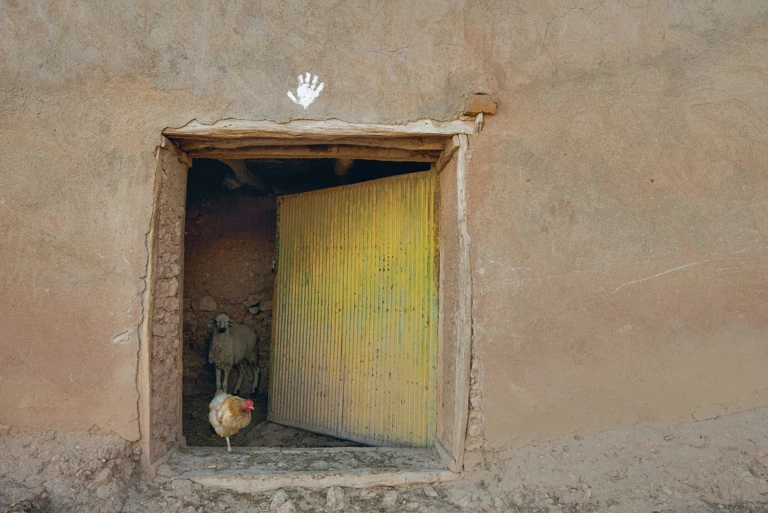

A chicken and a sheep prepare for their daily wanderings in the village of D’ouzrou. Photo: Leslie Kehmeier

Stretching for over 1,200 miles along Africa’s northern rim, the Atlas is a spine of peaks, some reaching over 12,000 feet, dividing the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea from the sweltering vastness of the Sahara Desert. The Amazigh have long called the Atlas home; by the time invading Arabic armies dubbed them “the Berber,” they’d been living in the range for more than 1,500 years. The Amazigh do not use the term, as it’s derived from the word “barbarian.” They do, however, still use the network of trails webbing their home mountains, one sculpted over generations. These pathways served as the first trade conduits between West and sub-Saharan Africa. Mostly they are the result of necessity, their purpose being to move and connect people of this steep, dry world.

From what we’ve heard, that purpose translates to world-class single track. With bicycles as our vehicles, we set out in September 2018 to explore the platform for life in the Atlas.

The late King Hassan II is said to have called Morocco “a tree whose roots lie in Africa, but whose leaves breathe in Europe.” Pedaling down Marrakech’s colorful, palm tree-lined streets shortly after our arrival, we quickly feel the truth of such a statement. A cloud of French, Spanish and Arabic swirls with smells from food carts.

Caution: one-lane road ahead. Bruntz, Pierre-Alain Renfer and Kehmeier navigate a back alley in the village of D’ouzrou on their way to the next section of Moroccan single track. Photo: Leslie Kehmeier

With nearly one million citizens and a bustling tourism industry, Marrakech is one of Morocco’s cultural hubs, and the country itself is largely Islamic. The city is home to multiple universities, museums and theaters. Women regularly go without veils, and in the more urban zones you’ll find younger women in bars. In 2009, the city elected a female mayor, the then-33-year-old Fatima Zahra Mansouri.

The city’s most famous cultural symbol, nevertheless, is ancient: the Medina, a 1,000-year-old city in the heart of larger Marrakech and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Medina is surrounded by red stone walls, but inside are wonders like the Koutoubia Mosque, with its 250-plus-foot minaret; the walls and gardens of the Kasbah; and the abandoned ramparts of the Badiâ Palace. We wander the narrow, windy streets lined with crafts and vendors, stopping to try fish dishes from the Atlantic coast.

We spend the next morning spinning out our jet lag in the nearby Agafay Desert before migrating toward the mountains. It’s early fall, and we’ve been advised the returning rains will dramatically improve the quality of the trails and revitalize the crops and vegetation. As the desert fades into foothills, we pass through fig, argan and olive orchards, and forests of cork, oak, pine and cedar, their freshened greenery contrasting with the red soil.

Small shops spring up along the road, marking our entrance into the Ourika Valley. Groups of tourists buy tagines, argan oils and “adventure camel rides,” but we’re here for the trails falling off the nearby mountain passes and spend the next few days devouring easily accessible single track. That’s just a taste, Pierre-Alain tells us. It’s time to go deeper.

Pierre-Alain would know. The Swiss cyclist first visited Morocco in 1990 for a mountain bike race and moved to Marrakech in 1992. Using his experience leading bike trips in France, Switzerland and Italy, he spent the 1990s pioneering mountain biking in the area, and in 1999 started his own company, Marrakech Bike Action. Since then he’s guided athletes like world champion Fabien Barel and freeride icon Mark Weir.

On the way to the souk in Amizmiz, Bruntz navigates the final stretch of trail, an incredibly elaborate creation that would cost $85,000 per kilometer to recreate in the United States. Photo: Leslie Kehmeier

The “deeper” to which Pierre-Alain is referring is the intricate single track connecting the High Atlas’s small but omnipresent villages. Perched on the steep mountainsides and surrounded by stepped fields of corn, squash and potatoes, the family dwellings are built from a mixture of clay, straw and water, and hug the walls of their neighbors in tight clusters. The colors of the villages wander with the hillsides; as the clay is sourced locally, the structures match the hue of the soil on which they’re built. A red village sits next to a khaki one, which sits next to a yellow one. The concrete mosques, painted a light rose, stand out among the harmonized homes.

Our destination and base for the remainder of the trip is La Bergerois de Ali, a stone sheep-barn-turned-guesthouse above Toulkine, a village hovering at an elevation of over 6,500 feet. Mount Toubkal, at 13,665 feet, the country’s and range’s tallest peak, dominates the horizon. Our eyes, though, are focused downward, at the single track leading away from our quiet oasis.

Trails remain an integral mode of travel in this part of the High Atlas and often more directly connect the villages. They have a natural efficiency achieved by centuries of foot traffic and are precise, intricate creations draped across the steep, rocky hillsides.

The Amazigh have been grazing sheep and goats and farming the Atlas Mountains’ arid soil for perhaps millennia, even as Roman, Arabic, Islamic, French and Spanish influences swept through the region, often violently. The majority of Amazigh practice an orthodox Sunni Islam, but much of this traditional lifestyle remains; Tamazight, their native language, is still common.

While riding through the village of D’ouzrou, Hamid Ashtouk invited the crew into his home for a breakfast of “Amazigh omelets,” a stew of eggs, tomato and onion prepared in clay cones called tagine. Photo: Leslie Kehmeier

They also build nearly indestructible trail. Rock retaining walls, some as high as 8 feet, hold precarious sections in place. On others, slabs of stone protect the surface from heavy erosion or heavily laden pack animals. The routes strategically contour the rolling hills, using the topography to achieve grades ideal for human and animal traffic. Many modern trail-building techniques have evolved from masterpieces like these, and for good reason: Chris has built trail around the world and estimates that replicating the most intricate sections in the United States would cost $85,000 per kilometer.

Between the stunning rockwork, the trail surface changes from black, dice-shaped scree to compacted red soil and everything in between. Some sections are raw and rutted, but I am taken aback by the flowy sensation most of the trails provide. It’s reminiscent of Colorado and parts of Utah and Arizona: red earth, canyon walls, rock features and incredible mountain biking.

As we navigate this complex web of dirt, I realize how difficult it would be without PierreAlain’s deep knowledge of the region, coupled with his ability to speak Arabic, French and Tamazight. There is, Pierre-Alain tells us, a simple way to find the best trails for bikes: Ask where the mules go. Often the most imperative to trade and travel, these sections tend to be the most meticulously cut and better maintained.

We see little traffic beyond the occasional local traveling by donkey, by mule or on foot,or shepherds herding sheep and goats on the surrounding hillsides. Riding through villages, the townspeople watch us curiously from their doorways. Laughing kids run alongside, greeting us with high-fives and “bonjour” or “salaam,” reflecting the area’s French and Arabic influences. Each time we wave and echo their greetings, exchanging kindness for kindness the best we can.

In one village I meet a young girl named Hanna, who leads me by the hand to a nearby walnut tree. She grabs a few black shells, knocking them on a rock to reveal rotten walnuts in each. Then she gestures higher, to the green shells out of her reach. I grab one and break it open. Inside is a moist walnut, big enough to share. Which we do.

Different hooves, same pathways. Many of the best trails for mountain biking in the High Atlas were stomped in by centuries of donkey and mule shoes, and the animals are still a favored mode of transportation. Photo: Leslie Kehmeier

I imagine Hanna walking to school on the trail I just descended, but when our guide Hassan asks her about it, she vigorously shakes “no” with her head and finger. That’s only for boys. More girls and children are attending school in the rural parts of the Atlas, but it remains a challenge. Hanna sends me off with a massive smile.

The next morning is our tagine breakfast at Hamid’s home, where we meet Samir to lead us on his new ride. Full from the decadent meal and multiple pots of tea, we spend the next hour climbing a dirt road before dropping down a scree mountainside. The bench-cut trail is exhilarating, narrow, exposed and broken up by tight switchbacks. Fresh to the sport or not, Samir knows how to choose an exploratory mission.

The Atlas may not be a mountain bike destination, yet a tight mountain bike culture is growing across the country. It’s why Aimad Laaouane founded Association Nationale de VTT, a Marrakech-based advocacy organization.

Aimad hopes to one day host internationally recognized mountain bike events in Morocco. He tells me about the annual three-day bike camp he puts on in the Atlas Mountains: This past year, 150 Moroccan mountain bikers attended. It’s an opportunity for new riders to learn together and explore this emerging theme of trail-based recreation, tying together past and present along the Atlas’s ancient pathways.

Our final ride of the trip drops us all the way to Amizmiz, a town of some 15,000 people in the northern foothills. Amizmiz serves as a hub for the many smaller settlements in the region, and each week villagers come from over 10 miles away to purchase items and sell goods at the souk, or weekly market. Many take the same paths we are now riding, and their mules and donkeys are loaded with crops and livestock to sell. One mule we pass is carrying a goat.

The tranquility of the mountains makes the bustling town seem even livelier. More laughter and conversation welcome us. Baskets bulge with olives, figs, apples, cucumbers and squash. Fresh cuts of meat hang from ceilings. Vehicles crowd the roads, making for a difficult readjustment. We hear the Islamic call to prayer and sit in a crowded restaurant for tagine and mint tea, staples since day one. We celebrate days of discovery and miles of mule-cut trail, raising a toast in gratitude to the people of the Atlas Mountains: “sow, gow, ich.”

This essay was featured in the Spring 2019 Patagonia Journal.