Under the Midnight Sun: A Paragliding Traverse of the Alaska Range

To understand this story you have to understand that I’m not crazy. Sure I’ve had some close calls, but that doesn’t mean I’ve got a death wish. There was that time in Mexico when I got stuffed in a waterfall kayaking a first descent and spent over five minutes underwater. And there was the time we got knocked down and nearly run over by an ocean freighter sailing in hurricane force winds and 35-foot seas off Cape Mendocino, California. Ah, and there was that time I landed my paraglider in a river above a heinous waterfall in the Dominican Republic, that was a close call for sure. And I do have to admit to spending a particularly spooky 10 hours swimming in a Pacific atoll filled with sharks after a night-dive went really wrong. And I really got close that time my kite exploded in a howling gale kitesurfing in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland forcing me to dump my gear and swim for several hours in 10°C water against the wind to make landfall. But I promise I didn’t do any of these things for the adrenaline rush. And I didn’t do them because I’m careless, or because I didn’t understand the risks. By definition, expedition means going into the unknown. By definition, adventure means something is going to go wrong. What I’m guilty of is sometimes pushing too hard. And sometimes I’m probably guilty of dreaming a little too big.

But that’s the thing about setting out to pursue your dreams. When you take the leap and pull it off it sets a precedent. It builds confidence, and because we are human and are inclined to want more, we want more. Young children think that anything is possible because they haven’t been told yet that it isn’t. They don’t fully understand the consequences. Why not jump? Time and school and adults and society and all the other things that shape us inevitably erode our compulsive curiosity and limitless confidence and something terrible happens: we stop dancing naked in front of everyone because instead of being impulsive and fun it becomes embarrassing. And I suppose … illegal.

I tried to fit in; I tried to tow the line. I got a job after university that required me to sometimes wear a tie and sometimes sit in an office. The office didn’t have windows and I was terrible at tying a tie, so I quit and went kayaking instead. I got pretty good at kayaking and started running rivers that were on the difficulty level where one wrong move could lead to serious consequences. After the Mexico episode I decided I should back off a bit, sail around the world and take like-minded adventurers kitesurfing instead. Other than the hurricane incident and a few mishaps with reefs and getting stranded on an island and spending a night with sharks it all went pretty well and I ended up going around the globe twice over a thirteen year span, visiting and in some cases living in some ninety-nine countries along the way.

Somewhere along the way I met a girl. All good stories have a girl. This girl handed me a paraglider and hucked me off a small hill in New Zealand. Which was unfortunate for the girl because the paraglider became my one true love. I began flying everywhere I could. I soared above the Matterhorn in the Alps; woke up encased in ice near Manali in the Himalayas; rode camels to launch in the high Atlas of Morocco; traversed the long, serrated spine of the Canadian Rockies to the US border; and wound up the length of the California Sierras to the Oregon border, completing the longest vol-biv (French for “fly-camp”) that had ever been done. I left sailing and kitesurfing and kayaking and surfing behind because they aren’t as magical as flying. Navigating a flimsy piece of plastic and string across a mountain range using nothing but invisible thermals and your own skill is more implausible than the most vivid dreams.

View from the paraglider. Photo: Gavin McClurg

Six years ago I found myself riding shotgun in a Supercub canvas bush plane in the Alaska Range. My paraglider was in the back seat and my brother-in-law Kenny was at the controls up front. I’d never seen terrain like that in my life. Massive, jagged ice and snow-covered peaks stretched to the horizon and beyond and were only separated by deep meandering glaciers and thundering, silty rivers. There is no humanity; in fact there is nothing but raw, deafening, stunning and intimidating WILDerness. In the Alps there are gondolas and ski resorts and sign-posted hiking trails that lead to huts selling ice cream and espresso. In the Himalayas and Andes and Caucasus and Zagros mountains villages perch in the most unlikely places. But in the Alaska Range there is nothing but an unending hugeness. No roads, no trails, no villages, no people.

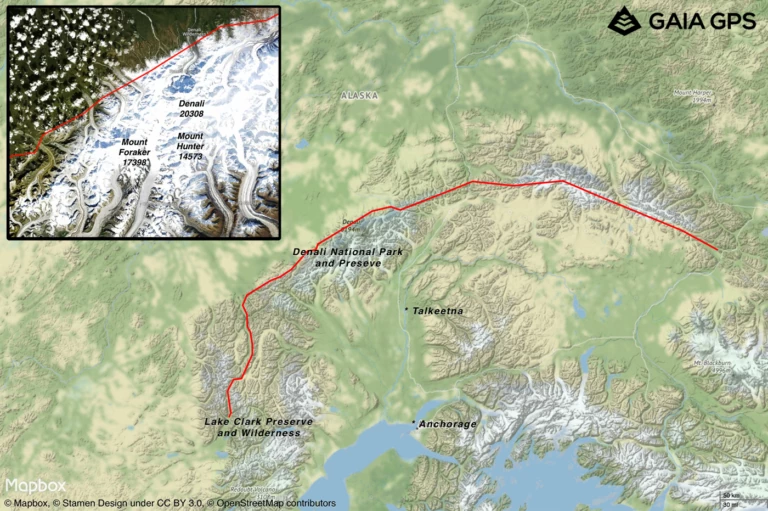

The range stretches 480 miles in a northward half-moon arc from west to east, bordered by the Aleutian range at one end and the Wrangell-St Elias on the other. It climbs to the highest point on the North American continent at Mt. Denali. At one point, we flew through a pass from the south side of the range to the north and suddenly the air got very turbulent. Turbulence means thermals and I got a half-baked idea that it may be possible to traverse the entire range by foot and paraglider.

Eventually the idea gelled into an obsession and I couldn’t stop imagining how flying over the range would feel. For a paragliding pilot I didn’t know of a bigger challenge. I told other pilots about my dream and the unequivocal response was that I’m crazy. But I’m not crazy, as I’ve already demonstrated! My friends pointed out that there are many reasons no one has attempted it.

“What about the bears?”

“How will you cross the glaciers and rivers?”

“It’s too far north!”

“How will you get across Denali National Park?” (It is legal to fly across U.S. National Parks, but illegal to launch or land in them).

Which just made me a lot more excited. No one has flown across one of the most iconic and remote mountain ranges in the world. I couldn’t think of anything that would be more magnificent and grand, and it hadn’t even been attempted! I studied weather patterns and maps and possible routes and some of the major hurdles like food. It would only be possible in May and June, during the longest days of the year. There is too much snow in April, and by July it’s too rainy. At that time of year you can’t legally hunt anything but bear, which isn’t very appealing; and the salmon aren’t high enough in the rivers, so I settled on putting in food caches in advance. There were a lot more questions than answers, and I worked on solving them for six straight years.

The idea takes shape. First glimpse of the Alaska Range from the Supercub. Photo: Gavin McClurg

May 14, 2016, Day 2

Soaked to the core we climb up out of the glacial-fed river onto a deep snow bank, our bodies shivering uncontrollably. My feet are completely numb as they had been for most of the day, a prelude to a condition we would battle for the coming weeks which would eventually lead to Trench Foot, a condition more common to people marching in a war than people just trying to have some fun. We’d been walking down the river for three hours because it was easier than the nine hours of post-holing across deep, completely rotten spring snow that preceded it. Post-holing, a term used to describe misery, is an activity whereby you walk one or two steps on top of deep snow, thinking you’ve finally found some stability and then WHOOSH, you break through the crust and sink up to your crotch or beyond and begin the whole process over, and over, and over again.

Sixteen hours of effort and we are less than two miles closer to our goal than we’d been that morning. Four hundred and seventy miles to go. We stomp out a couple of tent platforms, erect our thin houses and look at our dizzying surroundings. Fierce, absolute, merciless mountains loom at every point of the compass. It is as beautiful as it is daunting. I remove my frozen boots and assess my deteriorating feet and consider, for not the first or last time: What in the hell was I thinking?

Crossing another freezing river. Photo: Jody MacDonald

My partner Dave Turner stands nearly a foot taller than me. To keep up with his moderate walking pace I have to shuffle along in a near-run. “Solo Dave” got his nickname climbing some of the hardest and most-dangerous big walls on the planet—most of them alone. He spent 34 days in Patagonia ascending Cerro Escudo in 2008. To this day it’s the largest climb opened by a solo alpinist. He’s spent weeks alone on multiple arctic kite-skiing trips, living in the frozen darkness by a combination of ingenuity and skill and a monumental confidence in his own substantial abilities. He seems unfazed by our situation as he tucks into his sleeping bag, laughing as he unholsters a 40-caliber hand cannon and packs away his tenkara rod.

“Who takes a gun and a fishing pole on a paragliding trip?”

The gun is there not for hunting but protection. There will be no human trails on the entire traverse, but there are plenty of game trails. Sheep, moose, caribou, wolves, wolverines, fox and a lot more reside in healthy numbers across the range and grizzly bears are at the top of the food chain. Every “trail” we find has been used by bears. The meandering trails rarely take us in the direction we desire (I suppose because animals are not seeking paragliding launches), but they are easier to negotiate than bashing through endless dense alder forests, which is maybe the least-pleasant way of travel I have yet experienced in my forty-four years on Earth. By day five of the traverse, if you had offered me the option of walking barefoot through a sewer or bashing across another alder slope, I would have happily dove headfirst into the sewage and done the breast stroke.

When people move around Alaska they mostly do so by bush plane, not by foot or automobile. This is because the terrain doesn’t lend itself to walking, and there are very few roads. Dave has chosen to increase his chances by packing a gun. I’ve chosen bear spray, which a few days later we learn isn’t actually proper bear spray but protection spray, the kind people use in cities to keep bad guys at bay. It would indeed help in the event someone wanted to mug me in Alaska, but would be useless if a bear decided to make me dinner. I’ll have to stick pretty close to Dave.

We carry everything we need to survive in packs that weigh sixty pounds without water. This is not your standard backpacking kit. It includes our wings, harness, helmet, flying instruments, solar panel, tent, first aid and other safety gear, trekking poles, cooking kit and all the other essentials needed to survive and, more critically, nothing we don’t. Every ounce had been thoroughly considered. Can we take two pairs of socks or three? How about a second lighter? How much line in the repair kit? What belongs in the first aid? How much six-mil p-cord in case we land in a tree and need to rappel? One sewing needle or two? Every additional piece of gear we carry means we are less efficient on the ground, and less efficient in the air. A film crew is documenting the attempt, but we are accepting zero outside support.

Eating dinner and drying socks in camp. Photo: Jody MacDonald

June 7, 2016, Day 27, Heart Mountain

A foot and a half of snow has fallen overnight, but there really isn’t any night this far north. I shake my tent and unzip the door and look out across the expanse of the North Slope of Alaska and see something we haven’t seen much of for nearly a month. Bright blue sky and an unfiltered sun. We might finally get a chance to fly across Denali National Park, the crux of the expedition. Our camp is within meters of the park boundary at the west end and it is 110 miles in a straight line to the eastern boundary. We’ll cross all of the iconic peaks of the range: Hunter, Foraker and the tallest of them all, 20,320-foot Denali, if we can pull it off. If we can’t make it we’ll declare an emergency landing and have to walk the remaining distance, through an area one of the park rangers informed us before the trip was more populated with grizzlies than anywhere else in Alaska.

We’re nearly a month into the traverse and we’ve finished less than 25% of the route. A good deal of the time so far has been spent starving. On most days we burn thousands of calories in long pushes on the ground and replace a fraction of that with diminishing and inadequate food supplies. Much of our gear is broken and the alders have trashed most of our cloths. Dave and I spend most waking hours talking about food. As we wade across beaver dams, crawl through alder forests, slosh through swampy meadows and navigate over crevasse-strewn glaciers we talk about what we could eat if we could, and add to the growing list of what our first real meal will include when we get out. There have been a few glorious albeit short flights where we covered ground fast and with minimal effort. The flights lift our spirits, but more importantly they give us hope. The sun stays in the sky all day and the thermals are strong. If we can get some decent weather we can fly a long ways. But decent weather hasn’t been in long supply.

What we’re doing is totally experimental. None of the studying and planning we did before the trip have prepared us for the reality. None of the questions had answers until we began and most of them remain. None of our strategies have worked. We’ve tried waiting for good flying weather and conserved our food and energy. We tried pushing hard on the ground, burning up resources in the interest of ticking off miles. The only thing that has paid off is a belligerent stubbornness to keep pushing on. Dave and I have had a lot of disagreements but we’re holding it together as a team. We still believe it can be done.

Without proper flying conditions all you can do is walk. Photo: Jody MacDonald

We’ve been pinned down in our tents for eight days. I’ve been reading e-books, listening to podcasts, enjoying the silence and contentedly relishing how little there is to stress about other than just staying alive. There are no to-do lists to check off out here. No bills to pay, no emails to answer, no social media updates to craft. The largeness of Alaska is something that’s impossible to articulate. It catches me off guard every time I open my eyes. It makes me realize just exactly how inconsequential I am, how little I matter and how silly it is to worry about all the things we think are so important. Alaska doesn’t care that we are here and won’t care once we’re gone. I’ve had time to reflect, something I rarely do back in the “real world.” The reflection makes me wonder: Do we set out on expeditions to achieve something or do we set out on them to leave something behind?

We climb up through a thousand vertical feet of fresh snow and lay out our wings. Denali and Foraker beckon thousands of feet above us and to our east as rain clouds swell to our north. The bluebird morning is deteriorating rapidly but we have to give it a try. 1, 2, 3 … run.

This takeoff was almost flat, the snow was totally rotten and there was zero wind. We both did a couple solid faceplants before finally getting off the ground. Photo: Jody MacDonald

Imagine for a moment the highest mountains in North America towering above you. The snow and ice in some places are miles thick. The exposure and vertigo is on par with climbing Yosemite’s grand El Capitan but you’re in one of the most inhospitable places in the world. Denali is considered one of the coldest and cruelest alpine climbing objectives there is. Now imagine that you are flying, dangling under a piece of thin fabric with no sound but the wind and your variometer beeping as a strong thermal thrusts you into a dark cloud. You begin to shake with cold and you struggle to maintain your sense of direction and sense of up and down. Your eyeballs start to ice over. Everything is solid white; you are blind. At times you could swear your wing is below you but you remind yourself to breath and not to panic and focus on your compass and try to silence the screaming doubt in your brain. Finally you escape twenty agonizing minutes later. Your face and wing and harness are completely encased in rime ice. You get separated from your partner as you whisk past Denali, getting a brief glimpse of her glory as you hold your breath flying over yet another long, slithering perilous glacier. Was that the third or the fourth? Or maybe the sixth? The wind increases and so does your speed. The miles fly by.

An eagle spreads her wings mere feet from your wingtip and you climb together, circling round and round as the ground drops away. You’ve dreamt of this flight a million times. You’ve planned it. You’ve drawn the lines. Six years of wondering if it’s possible. You’ve put in thousands of hours of training for this one moment and now it’s happening. You know you will never do it again. It isn’t repeatable because no flight ever is. Every flight is unique, but this one hasn’t been done in any form, and it might not ever be repeated.

Flying past Denali. Photo: Jody MacDonald

June 13, 2016, Day 33, Panorama Mountain

When the weather finally broke I was alone. Dave had other commitments and was out of time, and the film crew was out of money. When everyone left we were only 60% across the traverse. We’d made it across Denali National Park, but the least-known part of the range lay ahead. I wasn’t ready to quit. If the outside world were allowed a brief glimpse into my own on the thirty-third day of the expedition my sanity would certainly be questioned. But like a great painting, on closer inspection another reality would emerge. Underneath the rotten feet and filthy cloths and broken gear was a guy living at a level of simplicity that is nearly impossible to achieve in today’s Ethernet-paced society. My muscles had adapted to the strain; my lungs were full of pure, clean air; my mind wasn’t clouded by frivolous responsibilities. I regaled in my one simple task, the task of staying alive.

Having a partner on a dangerous mission is important because it makes you feel a little less crazy. If there is someone else beside you sharing and suffering and risking his life along with you it makes you feel more confident that you haven’t gone off the deep end.

But paragliding is a distinctly solo sport. You and only you are the pilot in command and flying is not forgiving of mistakes. No one can save you if you screw up. There is no stop button. When you first learn to paraglide you fly established sites with reliable weather forecasts that have known launches and landings in conditions that suit your skill level. Often there are many other people in the air which helps you to find thermals and “read” the invisible air. When you land, you jump in a car or train or bus and go home. At the polar opposite end of the sport is flying across Alaska. There are no known launches and landings. Weather is deciphered on the fly because forecasts are meaningless. There is no history of other flights to follow. No track logs to study. The decisions are too many to list. Where to launch? Should I launch? Is it flyable? What route to take? What’s on the other side of that col? Is the wind getting too strong? Is the weather still safe to remain in the air? Should I land now or push on a little bit farther? How the hell do I get across that river? Holy shit that’s a big bear!

On one hand, when you are a team, making decisions is easier. You can talk it through, judge the plusses and minuses and find a consensus. On the other hand, the weight of making those decisions is heavier because if the decision is wrong it doesn’t just affect you, it affects your partner. Animosity is inevitable, even between good friends. Now that Dave is gone I miss having the comfort of his gun and his humor and most of all his friendship but now I can move at my own pace. My decisions only affect me. The reward of making a good call is more exhilarating, the price of making a bad call is easier to forgive.

The terrain takes on an entirely different character from the air. Photo: Jody MacDonald

Over the next four days miles tick by steadily as I fly in some of the strongest wind and most challenging conditions I’ve yet experienced as a pilot. I glide in step with an eagle over a twisted glacier above the Susitna drainage and have only my thoughts and a horizon that seems to stretch to eternity for company. I warily parallel a bear trail up a thrashing river and find an ice bridge to cross only to be boxed in by another river, which requires the most peculiar flight of my life to cross. I circle over a herd of caribou just feet off the ground before finding a thermal that carries me fifteen thousand feet skyward, where the beauty and rawness of the range reminds me to temper my elation even as it becomes obvious I will reach the end.

On the thirty-seventh and final morning of the traverse, as I was trying to find my way across yet another glacier, I kept reminding myself that reaching the end didn’t matter. It was the journey that mattered. That enjoying the solitude, breathing it all in and just being present was what really mattered. An overwhelming sense of gratitude took hold and I fantasized I could hold onto it forever. Gavin, when you get to the end, you don’t ever need to do anything like this again. You don’t need to take this kind of risk. You came up with this dream six years ago and now you’ve done it. Be happy with that. Be done now. Stop scaring your mom to death! This was my internal discussion. Be content. Be grateful. Be thankful. And I was, overwhelmingly so. When I landed at Mentasta Lake, the official end of the range, I was actually crying with joy. I thought I could pack up my wing, stick out my thumb, jump in a car and hold on to the feeling forever.

Flying over the Susitna and the West Fork Susitna Glaciers on the 37th and last day of the traverse. Photo: Gavin McClurg

Two hours later I sat in my tent and the gratitude and sense of accomplishment did the inevitable: It began fading away. I was already planning the next mission, wondering how I could “beat” Alaska. And then it hit me. And it’s not profound, nor is it new. Taking great risk, going on expeditions, doing things no one has done before, living a life of adventure is totally self-serving and really, completely meaningless. The Alaska traverse was outrageous and hard and absurdly fun, but it won’t better humanity and it won’t make the world a better place. But for me personally there was an unexpected takeaway that has grown stronger since that final day and it’s this takeaway that I believe makes expeditions and adventures worthwhile. Returning to the arms of my girlfriend, returning to the smiles of my friends, returning home makes me realize what’s really important. It makes me realize what I should really be grateful for. And it’s that lesson I will never forget.

Map courtesy of Gaia GPS.