After an Injury, Trying Really Hard Is a Beautiful Thing

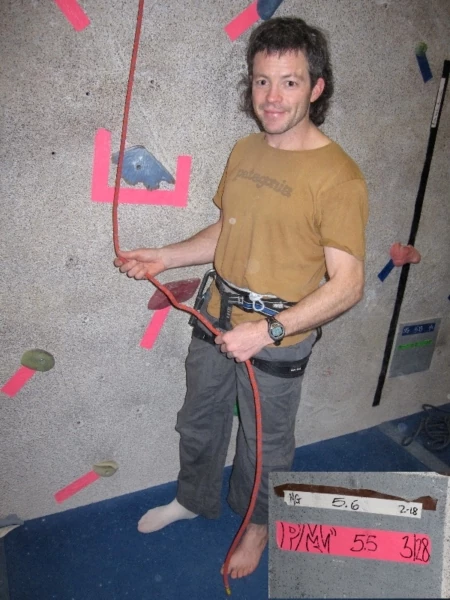

Over the years and all of these injuries, I’ve learned some things about success and failure. I’ve learned that there is one way, indisputable and proven through the ages, to ensure success. You lower your expectations. And so on my first day back climbing two weeks ago, I scanned the Boulder Rock Club for the easiest route – ah yes, there it is: Pink tape. Rating: 5.5. Just right for a man of my stature: Gimped, broken, mulletted and scared.

I look at the huge holds just as a big sound distracts me – a big guy, like real big, and 30 feet up on the route next door, on lead, thrutching, grunting, huffing and puffing. Big boy’s going for it.

I love people who try hard. The other shit doesn’t matter to me, at least not much, and not anywhere near as much as it used to. Give me an overweight beginner trying his damnedest on a 5.9 over some too-cool-for-school-attitude higher-numbered rock-jock (plastic-jock?) any day. It’s easy to get jaded when I visit Boulder, because the latter seems far too common, though it doesn’t matter and it shouldn’t annoy me like it does. After all, it’s just climbing (indeed pointing to my pathetic state). And, let’s not forget, not even real climbing, but gym climbing. Don’t get me wrong, I like gym climbing – it’s like a way better version of working out. Not the same as climbing outside, but I love pushing myself, even indoors, and it’s convenient and controlled. Go ahead, fine, yank my hardman-wannabe-alpine-toughguy membership card.

For me, trying hard increasingly means shifting my hammerhead mentality, being smarter, focusing on technique and sometimes doing less rather than more. More isn’t always better, although sometimes it is. You pick and choose, and maybe, as we go through life and hit our various roadblocks, we learn to choose with wisdom. Furthermore, we negotiate our worlds with a combination of individual drive and help from others. None of us stands alone, no matter how we try to convince ourselves, and sometimes we draw inspiration from the most unlikely places and people.

I told a buddy about how the big guy inspired me. He replied:

“I live with a clinical psychologist and she’s forever talking about what happens to people once they hit their 30s. Short version of the story: the frontal lobe of their brain completes its development, becomes fully attached to the brain, and in so doing, completes the process of ‘growing up.’ People start to look at the world with a perspective that’s no longer so ego driven, it becomes easier to see the beauty in things, and they open up to feelings like compassion and empathy in ways that are just plain beyond the ability of younger folks to understand.”

Uhhh, yeah dude. That’s exactly me. Yeeeish, I wish. Once they hit their 30s? How ‘bout 42. But hey, anytime my frontal lobe wants to attach itself to the rest of my brain I’ll take it.

Anyway, the big guy’s friend lowers him, still panting but genuinely psyched, and with a smile that fills the room. I nod, grin wide and say “good job,” before tying in and looking up. I honestly don’t think I’ve ever been nervous about 5.5. Especially on top rope. But it seems perfectly reasonable that, after six surgeries in thirteen months, some body part might snap off and fly into space. I’ve been cleared to ease back into climbing – in my last follow-up with my surgeon, who put back together nearly everything in my destroyed shoulder five months ago, he did this manual strength test and immediately gave a look of surprise you don’t often see from top-notch docs. “You’ve been working hard,” he said, nodding his head. A week later, my physical therapist measured my shoulder mobility and the same look crossed his face. “Wow. Full range of motion already. That’s incredible after all they did. Awesome.”

In both cases I think I glowed. Weird where we take pride, but indeed I have worked hard. (Hard to believe, given my aversion to work, but that’s a different kind of work.) It’s been the most painful and rigorous of all my recoveries, and one often laced with desperation and fear. I’ve done my work and I keep doing it. During the peak of rehab I spent up to 15 hours a week doing physical therapy, of which two hours were in the PT office, and the rest on my own, alone, self-motivated. (Granted, given all of my injuries, that equals like ten minutes per body part…). It’d be easy to convince myself that “it’s just climbing,” and use it as an excuse to avoid the pain of rehab, or to tell myself that I’m too busy. After all, climbing means nothing to the world; but it means something to me. So I make time and I try.

“OK, pink tape route, here we go,” I say with a smile, thinking about the guy one route over and how we all start somewhere, sometimes at different places in different times of our lives. One day it might be the pink tape route, and the next could lead to the Karakoram. I chalk up, double-check my knot and hear the comforting words of my partner. “OK,” she says, “I got you.”

Some low-lying crag peaks in the Karakoram Range, Pakistan. Photo: Kelly Cordes

Some low-lying crag peaks in the Karakoram Range, Pakistan. Photo: Kelly Cordes